By Christopher Cloutier, Naturalist (Morgan Arboretum, McGill University) and Teacher (Vanier College)

As a kid, growing up in the big city, wildlife was a rarity to say the least. Gray squirrels, starlings and house sparrows made up the “wild” critters around my childhood stomping grounds, but one group of organisms that never seemed to disappoint were the arthropods. Insects and spiders could be found virtually anywhere and it seemed that back then there were too many to ever count or name. It was from these early beginnings that I began to appreciate nature for both the big and the small. Cementing my interest in this amazing world of creepy critters were my early excursions to provincial parks and tagging along with naturalists who taught me more about these amazing creatures. Today, as an interpretive naturalist and teacher with a love of insects, it has become a passion and a joy to pass on the wonderment which is the “world of the little things” to people of all ages.

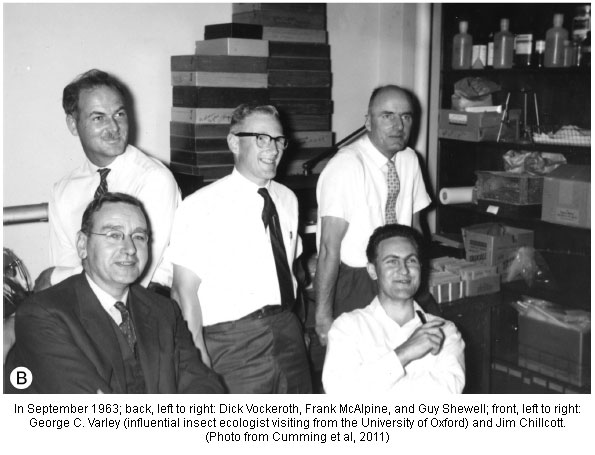

Reaching for the next pre-caught monarch to tag, Monarch Melee, 2011, Morgan Arboretum. Credit: Chris Cloutier

It is shown that insects generate a certain degree of interest from the layperson. Whether it be raising Painted Ladies in the classroom in elementary school, or counting the number of Plecoptera naiads during a stream survey; the fascinating life histories of insects have touched the lives of many people and have been used as a tool to emphasize the underlying principles of conservation, not only for the insects themselves but for the multitude of habitats which they occupy.

For years now I have led many insect-themed interpretive walks and have noticed a very strong showing from the general public. Children and parents alike seem to get the same level of enjoyment from spending an hour or two searching out and discovering something new about the world beneath their feet. With a fondness for Dragonflies, Butterflies and Spiders, these themed walks have become somewhat of a specialty and seem to attract more and more people every year.

One of the most enjoyable walks which has been held for three consecutive years now is entitled “Monarch Melee”. The activity is in association with the Monarch Watch program offered at the University of Kansas. The idea here, for those of you unfamiliar with the project, is similar to bird banding, except that the bands are stickers and the birds are, you guessed it, monarchs. I begin the workshop with a 30min presentation on the life history of the monarch butterfly, what it eats, metamorphosis, defense, and of course migration. It is amazing how a single insect, although quite charismatic for something other than a Panda or Beluga can make people so aware of the adaptability, perseverance and just general “wow factor” of insects as a whole. The presentation is followed by a tagging session for some pre-caught monarchs. Once the demo is over, we grab our nets and head out to several milkweed patches in search of more.

So, how does this sort of activity work to inspire people to do their part for conservation? Well, since those activities have been hosted, I know of several families that have since set up some very elaborate butterfly gardens at the homes, including puddling areas, butterfly shelters, hummingbird feeders, mason bee boxes, bat houses and more. People bring me photos of things that they are seeing around their homes, and not just Leptoglossus occidentalis photos anymore, but photos of butterflies and neat birds, spiders, and more. I have even seen kids walking around the Arboretum with binoculars and butterfly nets, yes, butterfly nets!

I feel that I have been able to open a door, or bridge a gap if you will, for some of these people to become enthralled in nature again, something which our current younger generation is having some difficulty doing. Although my personal role in this “nature revolution” is minor in the big picture, it is enormous in the lives of those inspired to learn more and to do more, just as it was for me when I was a kid. It never hurts to share your passion and of course a little knowledge. It might go a really long way (yes, Monarch migration pun intended!).

Photo: Reaching for the next pre-caught monarch to tag, Monarch Melee, 2011, Morgan Arboretum: credit: Chris Cloutier