By Dr. Chris Buddle, McGill University & Editor of The Canadian Entomologist

———-

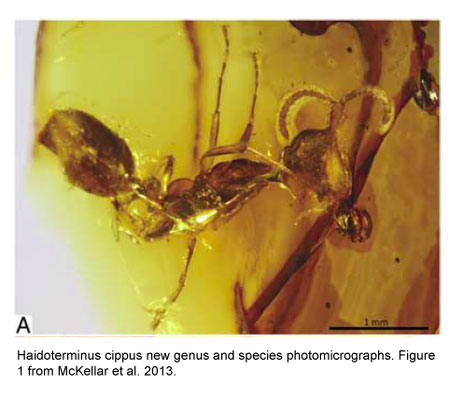

It’s with great pleasure that I announce my pick for the latest issue of The Canadian Entomologist. Ryan McKellar and colleagues wrote a paper on a new trap-jawed ant from Canadian late Cretaceous amber (freely available during September). As they write in the Abstract, the new species “….expands the distribution of the bizarre, exclusively Cretaceous, trap-jawed Haidomyrmecini beyond their previous records…”. They truly are bizarre! Facial structures right out of a sci-fi movie! When reading the paper, I was also surprised that the fossil record for the Formicidae is sparse during the Cretaceous.

I asked the lead author a few questions about this work, and am pleased to share the responses with you. It’s truly exciting research, and I am thrilled that the pages of TCE include systematics from amber. This work stirs the imagination, and takes us all back in time.

What inspired this work?

My interest in the Canadian amber assemblage really began when Brian Chatterton (then my M.Sc. supervisor) showed me some of the slides that he had borrowed from the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology in order to write a book on Canadian palaeontology. The sample set contained insects with bizarre adaptations for life at low Reynolds numbers, and obvious ecological associations, spurring an interest that ultimately led to a research in parasitic microhymenoptera. Michael Engel subsequently introduced me to a much wider array of taxa, and we continue to explore the Canadian assemblage together and with the help of colleagues.

What do you hope will be the lasting impact of this paper?

New records, such as this trap-jawed ant, help to flesh out our picture of the amber-producing forest and its inhabitants. I hope that a comprehensive account of this assemblage will eventually provide insights into terrestrial conditions that are unavailable from other fossil types, and that this will shed some light on changes in diversity and conditions leading up to the end-Cretaceous mass extinction.

Where will your next line of research on this topic take you?

With any luck, we will be able to complete our coverage of Hymenoptera in Canadian amber soon, and make more of a concerted effort to cover other insect orders and some of the ecological associations found within the deposit. Grassy Lake amber still has a lot to offer, but it is only one of western Canada’s many amber deposits. As a larger-scale project, we are currently part of a team examining the numerous fragile ambers associated with coals in the region. The goal of this research is to create an amber-based record of forest types and inhabitants that spans more than 10 million years within the Late Cretaceous and Paleocene.

Can you share any interesting anecdotes from this research?

Surface-collecting amber can be quite difficult, because unpolished Canadian amber typically has a matte orange-brown colour, and is often covered with a carbon film or weathering crust. If there is no fractured surface visible and the specimen is not translucent, it can be quite difficult to distinguish from the surrounding coal or shale. Furthermore, there is such a range of shapes and sizes that some of the smaller amber droplets are easily confused with modern seeds. One of the quickest ways to see if you are dealing with amber is to wet the specimen and look for amber’s characteristic lustre, or tap the specimen on your teeth (amber feels like plastic compared to most suspect rocks). Naturally, I have licked quite a few samples in the course of my collecting, and have lost a lot of my appreciation for rabbits.

Thanks to Cambridge Journals Online for making this month’s Editor’s Pick Freely Available for the month of September!

This post is a regular series highlighting great papers from the pages of the Canadian Entomologist.

McKellar R.C., Glasier J.R.N. & Engel M.S. (2013). A new trap-jawed ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Haidomyrmecini) from Canadian Late Cretaceous amber, The Canadian Entomologist, 145 (04) 454-465. DOI: 10.4039/tce.2013.23