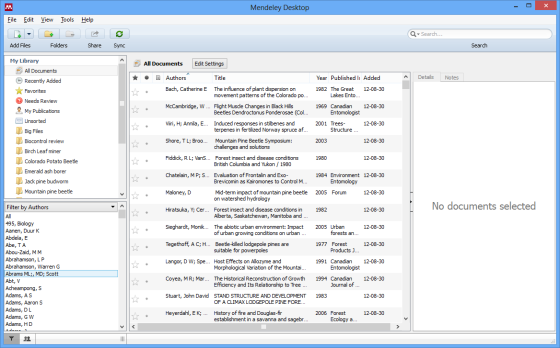

B. Staffan Lindgren is a professor of entomology at the University of Northern British Columbia, and 1st Vice-President of the Entomological Society of Canada. He has been the senior supervisor of 11 M.Sc. students and one Ph.D. student, co-supervisor of two M.Sc. students, and participated on more than 20 supervisory committees.

—————-

Recently I have been approached by several students asking about how to go about applying for graduate school. Furthermore, I and a colleague are doing a brownbag lunch discussion for the local student chapter of The Wildlife Society on this topic this week, and this got me thinking about what considerations a student should have. My conclusion is that you can break down the approach into a consideration of W5 (Why, Where, Who, What, and When) to optimize the chances of being successful.

In this post I will go over my thoughts on these W’s, and relate some of my own experiences, both as student and supervisor. I have not consulted the literature, but base this on personal experience alone, so you have to bear that in mind. For the record, I have not supervised a large number of graduate students, and all but one have been at the Master’s level. On the other hand, I have only “failed” as a supervisor once, which just means that I blame myself for the student’s failure to complete. On the other hand, I have also failed as a graduate student once, so I feel I have some relevant qualifications for writing this.

Why?

This question may seem somewhat redundant, but I believe it is an important first step. It is surprising how many students go into graduate school “to get a better job”. In my opinion, that is not a good reason at all. It is very possible, or in fact likely, that you can land a better job after completing a graduate degree, but there is no guarantee for advanced degrees automatically leading to better jobs. I have two examples. One of my more successful graduate students told me long after she graduated that she went into graduate school for this very reason. Somewhere along the way, she realized that she loved research, and her passion for it grew as a result. She subsequently carried on with a PhD, and now holds a very good research position. So in her case doing a graduate degree led to exactly what she set out to do to begin with, but it wasn’t graduate school per se that lead to her success, but rather her passion for what she was doing, along with some very hard work. My second example relates to my first, and failed attempt at graduate school. I was more worried about funding than topic, and opted to do a PhD in Endocrinology. I had really enjoyed my coursework in zoophysiology, so it seemed like a logical choice at the time. I was in a good lab, had a great colleague (who is now a professor with more than 300 authored or co-authored publications). As it turned out, it was not for me, however. The reasons were many, but a lack of passion for the subject area certainly contributed (see below).

Where?

Different institutions have varying reputations, and particularly if the ultimate goal is an academic position, it may make a difference whether you hold a degree from a major research university or primarily undergraduate teaching institution. However, there may be pros and cons with joining big labs. An obvious benefit is that a large institution is likely to have lots of infrastructure and resources. On the other hand, you may end up in a lab where your supervisor plays only a limited role in your actual supervision, i.e., you may be viewed more as a small cog in a large wheel than as an important individual. To avoid this, you have to ask the next question.

Who?

The supervisor is of critical importance in my opinion. All supervisors are not made equal, and they often have their own agendas and biases! Some may expect you to work things out for yourself, while others like to treat you like an employee. Depending on your personality, you may like one or the other, or somewhere in between. Highly productive, “big name” researchers are not necessarily the best supervisors! Moderately productive scientists at small institutions may provide a much better environment, particularly for graduate students lacking prior experience, e.g., Master’s students. I went into my first two graduate degrees (including the initial failed PhD in Sweden) pretty much blind. The endocrinology attempt was uncomfortable because of an internal schism between my supervisor and the head of the department, but other than that I was fortunate to get a very approachable and helpful supervisor. My supervisor for my Master of Pest Management and PhD degrees at Simon Fraser University was as good as they come; I learned an enormous amount from him, and model my own approach to supervision on that experience. However, he did not suit everybody. The problem is matching your own needs and preferences with a suitable supervisor. I recommend all prospective graduate students to contact both former and current students of potential supervisors and ask what it is like to be a graduate student. I even recommend students expressing interest in me as a supervisor to do the same – I think of myself as a good supervisor, but I am clearly biased, and in control of the situation, whereas a graduate student would be dependent on my actions. Raise up front issues of support (not just salary, but field assistant, transportation, accommodation in the field, expectations). Ask about how the supervisor deals with authorship – believe it or not, there are supervisors who are prone to self-promotion. A good supervisor promotes his/her students, not themselves. Once you are in a graduate position, it is much more difficult to adjust things, so do your homework up front. I also recommend students to be frank with a potential (or existing) supervisor if there are issues. If you can’t communicate with your prospective supervisor before you are his/her graduate student, it is likely that you won’t be able to later. Sometimes this is just due to personality incompatibility, but it really doesn’t matter what the reason is if you end up in a bad situation. You are never going to go into a graduate position with 100% confidence that it will be perfect, but you can optimize the chances that it will be by doing some basic research.

A successful supervisor-student relationship can turn into a lifetime relationship: Staffan Lindgren (PhD 1982), Lisa Poirier(PhD 1995) and Dezene Huber (PhD 2001), gave back to their supervisor John H. Borden by successfully nominating him for an honorary doctorate at UNBC in 2009 in recognition of his enormous impact on forest insect pest management in British Columbia. Photo by Edna Borden.

What?

This is perhaps the most important decision you have to make, and it is closely linked to the first W (Why?). In my experience, the most successful students are not those who come in with the highest GPA or with the most funding (although it is easier to get accepted with those qualifications as it relieves the supervisor of some obvious burdens). Rather, they are the students with a burning interest in a specific type of project, or specific organisms. A great way to find your bearings is to get involved in research as an undergraduate student. When I was a PhD student, I had three undergraduate research assistants over the years. All three went on to get a PhD, one is now a research scientist with Forestry Canada, one is a conservation biologist with a consulting company (after Environment Canada was brought to its knees by the current government), and the third is a professor at a large institution in the United States. A number of students I have hired as undergraduate summer research assistants have successfully pursued successful careers. Decisions you make as a young person can profoundly affect your future. I went to the United States as a high school exchange student – without that experience I may have lacked the confidence to come to Canada for graduate school. As an undergraduate student, I participated in annual vole surveys and spider research, which taught me something about what types of activities I enjoy. When I first wanted to pursue graduate school, I failed to use that experience. My primary interest was entomology, but funding was hard to come by, so I opted for endocrinology because that graduate position came with a stipend. This decision turned out to be a huge mistake, and after 1 ½ years I had to give up. Essentially, I selected what to do for the wrong reason. (Thanks to my brilliant graduate student colleagues, I still ended up with five publications, which probably helped me get accepted at Simon Fraser University, so it wasn’t a complete waste of time, however). At SFU, my MPM supervisor offered me a funded project that would have been applicable to Sweden, and he gave me 8 months to think about it. I eventually made the decision to take that on, and I have never looked back. Thus, once I reset the career compass to my original goals, I ended up where I always wanted to be, which is in forest entomology!

When?

Strangely, this question relates to both “Why” and “What”, although there is considerable variation among students in terms of what is right for each individual. In my experience, however, the most successful graduate students tend to have a little bit of “real world” experience before they pursue a graduate degree. In part, this may be because they have more experience, and therefore are more confident about their abilities, and possibly more aware of their weaknesses than someone fresh out of an undergraduate degree would have. These individuals have also had time to formulate what they are really passionate about, and in my mind, passion is the most important ingredient in a successful graduate degree. Yes, you need some basic skills (communication (written and oral), quantitative skills), a modicum of intelligence, and lots of patience for endless tedium (most research is 90% tedium, 5% frustration, and 5% elation), but you don’t have to be an A+ student. As a graduate student, a passionate B student will do better than a moderately interested A+ student any day. You would be surprised how many professors and successful scientists were relatively average in high school. If the timing is wrong, you may not be happy. For example, when I first tried to pursue graduate school and ended up in the wrong program, I could have waited 2-3 years and I may have had perfect opportunities in Sweden as a huge project on insect pheromones was initiated a year after I went to Canada. I had in fact contacted several of the professors that led that project, but at the time they didn’t have the funds in place.

I mentioned at the beginning that I failed as a supervisor once. This was a combination of not matching the student with an appropriate topic, and personal incompatibility. Both resulted from inexperience, as it was one of my very first graduate students. Even supervisors learn from experience.

I hope these musings are helpful you decide to pursue a graduate degree. Good luck!